Yesterday, we were all going to die because there would be no more bees.

Today, insects will all die because there are too many bees, or something.

Analysis by Andrew Van Dam: Hidden deep within the latest Census of Agriculture lurks a shocking fact: The United States has more bee colonies than ever before. https://t.co/7gYc32LzcD

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) March 30, 2024

It turns out that neither assertion is true.

The beepocalypse was always a manufactured panic, although a rather profitable one for a small slice of the population who “consulted” on how to save the bees. Environmentalists loved the story because it provided another angle to attack industrial agriculture. And, of course, for the media, which regularly push false narratives to keep us excited.

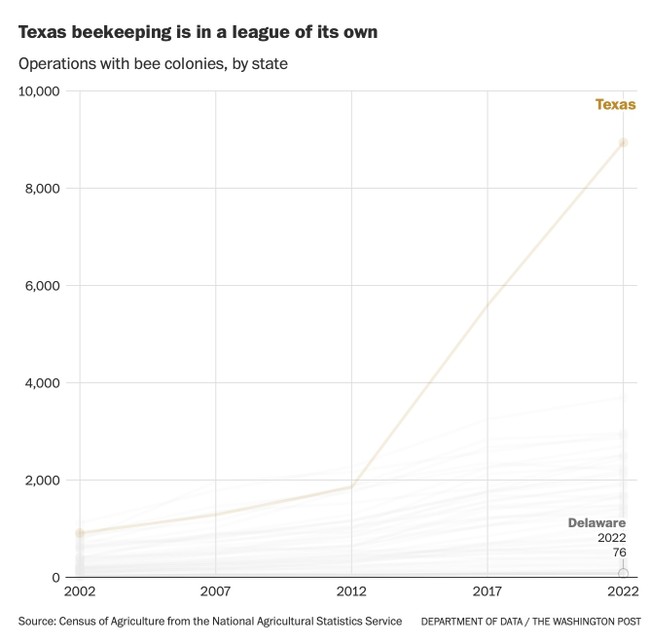

The Washington Post presents a fascinating observation: never before in American history have there been more bee colonies. This intriguing trend, like many others, is a product of economic forces.

Back in the aughts, you couldn’t get away from the beepocalypse story, and in certain circles it continues to be pushed. Environmentalists testify at legislatures with scare stories about the lack of pollinators and the coming collapse of agriculture. And tax breaks for planting flowers at solar farms popped up. Bees dying provided jobs and fodder for lobbying.

None of it was true. There was, indeed, an epidemic of colony collapse syndrome during the Bush administration, but it turns out that colony collapse syndrome goes back as far as records of bee colonies do. It apparently is cyclical, and nobody knows why.

After almost two decades of relentless colony collapse coverage and years of grieving suspiciously clean windshields, we were stunned to run the numbers on the new Census of Agriculture (otherwise known as that wonderful time every five years where the government counts all the llamas): America’s honeybee population has rocketed to an all-time high.

We here at the Department of Data are dedicated to exploring the weird and wondrous power of the data that defines our world.

We’ve added almost a million bee colonies in the past five years. We now have 3.8 million, the census shows. Since 2007, the first census after alarming bee die-offs began in 2006, the honeybee has been the fastest-growing livestock segment in the country! And that doesn’t count feral honeybees, which may outnumber their captive cousins several times over.

Feral honeybees. I love it.

Bees are an important business sector for obvious reasons, and some people make a living less by producing honey than by raising bees to pollinate crops. Especially almonds, it turns out, because they are hot right now. Almonds are seeds, and they exist because bees pollinate almond flowers.

I never thought of that, but it is obvious in retrospect. Of course, I rarely think of bees unless I am near a bunch of them, because I developed and allergy to their stings. Bees, though, aren’t mean like hornets, so even then I am only mildly interested in them.

It turns out that the explosion in the number of bee colonies has little to do with honey or even professional pollination.

It’s taxes in Texas.

Dennis Herbert wouldn’t strike you as a political mover and shaker. A retired wildlife biologist, Herbert, 75, boasts of no fancy connections and drops no names. But in 2011, after keeping bees for a few years, he went to the Texas legislature and laid out a simple hypothetical.

“You own 200 acres on the other side of the fence from me, and you raise cotton for a living. You get your ag valuation and cheaper taxes on your property. I have 10 acres on the other side of the fence and raise bees, and I don’t receive my ag valuation. And yet my bees are flying across the fence and pollinating your crops and making a living for you,” Herbert said. “Well, I just never thought that quite fair.”

In 2012, the Herbert Hypothetical gave rise to a new law: Your plot of five to 20 acres now qualifies for agriculture tax breaks if you keep bees on it for five years.

Over the next few years, all 254 Texas counties adopted bee rules requiring, for example, six hives on five acres plus another hive for every 2.5 acres beyond that to qualify for the tax break. Herbert keeps a spreadsheet of the regulations and drives across the state to educate bee-curious landowners.

Bee-curious will soon be a new stripe on the ever-growing Pride flag, I am sure.

All this matters, of course, because the non-existent beepocalypse spurred limits on neonicotinoid insecticides. For instance, in the EU regulations were put in place to save the bees.

In 2013, five neonicotinoid insecticides were approved as active substances in the EU for the use in plant protection products, namely clothianidin, imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, acetamiprid and thiacloprid.

The Commission closely monitors the possible relations between bee health and pesticides and is determined to take the most cautious approach possible to protect bees.

In 2013, the Commission severely restricted the use of plant protection products and treated seeds containing three of these neonicotinoids (clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam) to protect honeybees (see Regulation (EU) No 485/2013).

The measure was based on a risk assessment of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2012. It prohibits the use of these three neonicotinoids in bee-attractive crops (including maize, oilseed rape and sunflower) with the exception of uses in greenhouses, of treatment of some crops after flowering and of winter cereals.

At the same time, the applicants of the three substances were obliged to provide further data (so-called “confirmatory information“) for each of their substances in order to confirm the safety of the uses still allowed.

Following the assessment of this confirmatory information by EFSA of clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam, the remaining outdoor uses could no longer be considered safe due to the identified risks to bees. Therefore, the Commission services prepared in 2017 three proposals to completely ban the outdoor uses of the three active substances.

Search Google and you will see an unending list of attacks on these pesticides, mostly linked to how they kill off bees. Ironically, of course, we know that this is overblown because honeybees are constantly pollinating agricultural products using these insecticides, and there are a record number of hives and bees.

It stands to reason that both things can’t be true. Certainly, neonics might have an adverse impact on bee health, but the far larger problem turns out to be parasites. And, obviously, bees are weathering the storm nicely.

Generally speaking, most panics are the equivalent of hoaxes. Some modest, everyday problem is hyped endlessly, getting people worked up. Grifters grab onto it to make a buck or raise their profile. It generates clicks and watches. And somebody is identified as causing a nonexistent or tiny problem.

The lesson is to distrust the stories about killer bees, murder hornets, or just about anything else that is supposed to panic you. Sometimes there is a real problem, but rarely a crisis.

But for some the crisis is the point, because you should never let a crisis go to waste.

Read the full article here